Stars, Hearts and Forcing Emotion Where There Is None

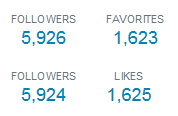

On Tuesday, Twitter made a seemingly small, but not quite insignificant change. They replaced the star icon with a heart. The tweets that had been marked as “favorites” previously, were now marked as “likes.”

On Tuesday, Twitter made a seemingly small, but not quite insignificant change. They replaced the star icon with a heart. The tweets that had been marked as “favorites” previously, were now marked as “likes.”

Twitter released a video when they announced the change (embedded below), where they provided a sample list of emotions and statements that could be indicated by using the heart icon. These included “yes!,” “congrats,” “LOL,” “aborbs,” “stay strong,” “hugs,” “wow,” “aww” and “high five.”

Whenever Twitter makes a change, there are complaints. That doesn’t mean the change isn’t worthwhile. And I’m not here to tell you this is a big deal. However, I do think there are some interesting dynamics at play, especially when it comes to how we manipulate user intent by retroactively applying new labels to previous user actions.

You can say a lot with a heart. Introducing a new way to show how you feel on Twitter: https://t.co/WKBEmORXNW pic.twitter.com/G4ZGe0rDTP

— Twitter (@twitter) November 3, 2015

A Different Emotion

Favorites aren’t likes. That seems pretty straightforward. While using the star to indicate that you like something is a popular use, there are also other popular uses. Here are two I’d like to focus on:

- Acknowledging that you have viewed a message. This is pretty common among professionals. Essentially: “I saw your message, and don’t have anything to add.” This is not a sign of agreement or disagreement, but of respect (more on that in a moment).

- Bookmarking something for later reference. This is a neutral action, as you could be documenting something great, horrible or in between.

Because the star was flexible and generally emotion-neutral – especially as compared to a heart – people have applied different meanings and contexts to it.

Earlier this year, Twitter investor Chris Sacca argued that the “favorite” terminology was too strong and that hearts were more “casual.” He wrote:

Favorite Is Too Strong A Word – A very high bar is set by using the word “Favorite” on Twitter. Favorite is a superlative. It implies a ranking. In the early days of Twitter many of us interpreted the word literally and only keep a few Tweets in our favorites that were truly, well, our favorites. Today, many of my friends and I use the star as a “Like” button equivalent or even a simple acknowledgement that we saw a Tweet. Whereas other people use favorites as bookmarks. However, the majority of users are baffled by favorites and they don’t end up using the star much, if at all.

Bring On The Hearts – It is high time to introduce “Hearts” to Twitter. For years, folks at Twitter struggled with whether to use a more casual gesture. Suggestions even included buttons that said “Good” or “Thanks.” It is now clear from across the Internet and throughout the world of apps that the heart is universally understood and embraced. (In fact, Periscope’s unlimited heart repetition has elevated the social feedback loop to a mind-blowing new level.) If Twitter integrated a simple heart gesture into each Tweet, engagement across the entire service would explode. More of us would be getting loving feedback on our posts and that would directly encourage more posting and more frequent visits to Twitter.

I’d be curious to see these thoughts backed by surveys with internet users (of all ages). I don’t know that people view the word “favorite” as a ranking – in the context of a software feature, anyway. When many people think of favorites in that light, they think of bookmarks. There is a long history of this usage online. The word “favorite” on a device simply does not have the same meaning as you asking someone, “what’s your favorite movie?”

If you asked a sampling of internet users to define the meaning of a “heart” icon, what would they say? My feeling is that they would take it to be more closely associated with “love” or loving something, not with “like,” “good,” “thanks,” bookmarking or acknowledging.

The Retroactive Heart

If you have an issue with this change, it’s quite likely that your criticism is due to them retroactively applying an emotion to your content that you didn’t want to express at the time. The hearts on Instagram aren’t an issue, because hearts didn’t replace anything on Instagram. They were simply there. The same is true for hearts on Periscope. They have always just been there.

But Twitter is a mature platform, where people have used the star icon for years, and a societal norm has formed. It is worth questioning Twitter’s choice to go back and retroactively apply a new label to past user behavior. The decision to do that, instead of leaving stars alone and introducing hearts as a new microaction, could be taken in a disrespectful light.

It reminds me of the Flickr auto-tagging issue. Flickr went back and added new, automatically-generated tags to previously uploaded photos. Did these tags improve the user experience? Quite possibly. When the tags were accurate, they helped people to more easily find the photos they were looking for. But many members of the Flickr community are protective of their photo pages, and how their content is tagged and titled.

Similarly, a Twitter profile is something we create. A curated representation of who we are, that can include favorites that may not always be made in the vein of “loving feedback.” Someone at the center of a social uprising may be documenting tweets posted by the opposition. Do you want to heart that? Do journalists want to heart tweets they are saving to reference in a story?

The Respect Button

The Engaging News Project found that changing the “like” button to “respect” can have a positive impact on the level of discourse in comment sections. That neutrality is something that Twitter has lost here. You can retweet, heart, respond or simply ignore it. Those are your choices. If I want to tell someone I respect their view, even if I don’t agree with it, I’m not sure the heart button is a good choice for that, where a star could have been.

As Sacca said, hearts are “loving.” But bookmarks and acknowledgements aren’t necessarily meant to be.

Is It Bad for Twitter?

No, not really. The fact is, people didn’t ask for Twitter’s permission to use the star how they did. They won’t necessarily care how Twitter suggests they use the heart. Some will alter their behavior, but plenty will just do what they did before. When you boil it down, it’s just a feature that allows you to mark tweets. Using it as a bookmark or acknowledgement will just water down the meaning of “heart,” whatever that is, making it more of a neutral thing and less of a “loving” thing.

If, as Sacca suggests, a heart makes new and uninitiated users more comfortable, that’s a positive. Sacca retweeted a message that dismissed complaints about the heart as being from power users that didn’t fit the general audience that Twitter is pushing for.

https://twitter.com/MikeIsaac/status/661636423917940737

That is possibly so. Complaints are a part of all change, even change that works out wonderfully.

My point is less about Twitter, and more about those of us who manage online communities and social spaces where people engage. We have to be careful not to be too cavalier. Regardless of how well this works out for Twitter, it’s worth considering how your users make use of current features and trying your best to ensure that changes to those features do not retroactively degrade their previous intention. We have to treat member content – and the meaning behind that content – with the utmost respect, and not take it for granted in the endless user acquisition quest.